Content from Introduction to Omics Translation in AD

Last updated on 2026-03-03 | Edit this page

Introduction

This workshop will deliver hands-on training using the most recent computational techniques and omics data resources to improve awareness and utility of integrating multi-scale data from model systems and humans to uncover the mechanistic drivers of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD).

Despite considerable effort in drug development for AD, high rate of failure in clinical trials emphasize the need for more effective preclinical strategies, including targeted use of mouse models to study heterogenous disease phenotypes. In this era of omics-driven research, interspecies alignment of disease relevant molecular signatures relies heavily on bioinformatics tools and field-specific data infrastructures.

The goal of this workshop is to accelerate translational research in AD by training interested scientists on how to develop robust computational workflows for both hypothesis-driven and data-driven research strategies. The AD-specific, bespoke lessons will use resources from the AD Knowledge Portal, a NIA designated FAIR data repository that shares data from human and non-human studies generated by multiple collaborative research programs focused on aging, dementia, and AD.

Lesson material

Here are the R scripts and data files used in this workshop.

Content from Synapse and AD Knowledge Portal

Last updated on 2026-03-03 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How can we work with the Synapse R client?

- How can we work with data in AD Knowledge Portal?

Objectives

- Explain how to use

SynapserPackage. - Demonstrate how to locate data and metadata in the AD Knowledge Portal.

- Demonstrate how to download data from the AD Knowledge Portal programmatically.

Working with AD Portal metadata

We have now downloaded several metadata files and an RNAseq counts file from the portal. For our next exercises, we want to read those files in as R data so we can work with them.

We can see from the download_table we got during the

bulk download step that we have five metadata files. Two of these should

be the individual and biospecimen files, and three of them are assay

metadata files.

R

download_table %>%

dplyr::select(name, metadataType, assay)

We are only interested in RNAseq data, so we will only read in the individual, biospecimen, and RNAseq assay metadata files.

R

# counts matrix

counts <- read_tsv("data/htseqcounts_5XFAD.txt",

show_col_types = FALSE)

# individual metadata

ind_meta <- read_csv("data/Jax.IU.Pitt_5XFAD_individual_metadata.csv",

show_col_types = FALSE)

# biospecimen metadata

bio_meta <- read_csv("data/Jax.IU.Pitt_5XFAD_biospecimen_metadata.csv",

show_col_types = FALSE)

# assay metadata

rna_meta <- read_csv("data/Jax.IU.Pitt_5XFAD_assay_RNAseq_metadata.csv",

show_col_types = FALSE)

Let’s examine the data and metadata files a bit before we begin our

analyses. We start by exploring the counts data that we

read in using the tidyverse read_tsv()

(read_tab-separated values)

function. This function reads data in as a tibble, a kind of

data table with some nice features that avoid some bad habits of the

base R read.csv() function. Calling a tibble

object will print the first ten rows in a nice tidy output. Doing the

same for a base R dataframe read in with read.csv() will

print the whole thing until it runs out of memory. If you want to

inspect a large dataframe, use head(df) to view the first

several rows only.

R

counts

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 55,489 × 73

gene_id `32043rh` `32044rh` `32046rh` `32047rh` `32048rh` `32049rh` `32050rh`

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 ENSG00… 22554 0 0 0 16700 0 0

2 ENSG00… 344489 4 0 1 260935 6 8

3 ENSMUS… 5061 3483 3941 3088 2756 3067 2711

4 ENSMUS… 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

5 ENSMUS… 208 162 138 127 95 154 165

6 ENSMUS… 44 17 14 28 23 24 14

7 ENSMUS… 143 88 121 117 115 109 75

8 ENSMUS… 22 6 10 11 11 19 24

9 ENSMUS… 7165 5013 5581 4011 4104 5254 4345

10 ENSMUS… 3728 2316 2238 1965 1822 1999 1809

# ℹ 55,479 more rows

# ℹ 65 more variables: `32052rh` <dbl>, `32053rh` <dbl>, `32057rh` <dbl>,

# `32059rh` <dbl>, `32061rh` <dbl>, `32062rh` <dbl>, `32065rh` <dbl>,

# `32067rh` <dbl>, `32068rh` <dbl>, `32070rh` <dbl>, `32073rh` <dbl>,

# `32074rh` <dbl>, `32075rh` <dbl>, `32078rh` <dbl>, `32081rh` <dbl>,

# `32088rh` <dbl>, `32640rh` <dbl>, `46105rh` <dbl>, `46106rh` <dbl>,

# `46107rh` <dbl>, `46108rh` <dbl>, `46109rh` <dbl>, `46110rh` <dbl>, …The data file has a column of ENSEMBL gene_ids and then

a bunch of columns with count data, where the column headers correspond

to the specimenIDs. These specimenIDs should

all be in the RNAseq assay metadata file, so let’s check.

R

# what does the RNAseq assay metadata look like?

rna_meta

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 72 × 12

specimenID platform RIN rnaBatch libraryBatch sequencingBatch libraryPrep

<chr> <chr> <lgl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr>

1 32043rh IlluminaN… NA 1 1 1 polyAselec…

2 32044rh IlluminaN… NA 1 1 1 polyAselec…

3 32046rh IlluminaN… NA 1 1 1 polyAselec…

4 32047rh IlluminaN… NA 1 1 1 polyAselec…

5 32049rh IlluminaN… NA 1 1 1 polyAselec…

6 32057rh IlluminaN… NA 1 1 1 polyAselec…

7 32061rh IlluminaN… NA 1 1 1 polyAselec…

8 32065rh IlluminaN… NA 1 1 1 polyAselec…

9 32067rh IlluminaN… NA 1 1 1 polyAselec…

10 32070rh IlluminaN… NA 1 1 1 polyAselec…

# ℹ 62 more rows

# ℹ 5 more variables: libraryPreparationMethod <lgl>, isStranded <lgl>,

# readStrandOrigin <lgl>, runType <chr>, readLength <dbl>R

# are all the column headers from the counts matrix

# (except the first "gene_id" column) in the assay metadata?

all(colnames(counts[-1]) %in% rna_meta$`specimenID`)

OUTPUT

[1] TRUEAssay metadata

The assay metadata contains information about how data was generated

on each sample in the assay. Each specimenID represents a

unique sample. We can use some tools from dplyr to explore

the metadata.

R

# how many unique specimens were sequenced?

n_distinct(rna_meta$`specimenID`)

OUTPUT

[1] 72R

# were the samples all sequenced on the same platform?

distinct(rna_meta, platform)

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 1 × 1

platform

<chr>

1 IlluminaNovaseq6000R

# were there multiple sequencing batches reported?

distinct(rna_meta, sequencingBatch)

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 1 × 1

sequencingBatch

<dbl>

1 1Biospecimen metadata

The biospecimen metadata contains specimen-level information,

including organ and tissue the specimen was taken from, how it was

prepared, etc. Each specimenID is mapped to an

individualID.

R

# all specimens from the RNAseq assay metadata file should be in the biospecimen file

all(rna_meta$`specimenID` %in% bio_meta$`specimenID`)

OUTPUT

[1] TRUER

# but the biospecimen file also contains specimens from different assays

all(bio_meta$`specimenID` %in% rna_meta$`specimenID`)

OUTPUT

[1] FALSEIndividual metadata

The individual metadata contains information about all the

individuals in the study, represented by unique

individualIDs. For humans, this includes information on

age, sex, race, diagnosis, etc. For MODEL-AD mouse models, the

individual metadata has information on model genotypes, stock numbers,

diet, and more.

R

# all `individualID`s in the biospecimen file should be in the individual file

all(bio_meta$`individualID` %in% ind_meta$`individualID`)

OUTPUT

[1] TRUER

# which model genotypes are in this study?

distinct(ind_meta, genotype)

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 2 × 1

genotype

<chr>

1 5XFAD_carrier

2 5XFAD_noncarrierJoining metadata

We use the three-file structure for our metadata because it allows us

to store metadata for each study in a tidy format. Every line in the

assay and biospecimen files represents a unique specimen, and every line

in the individual file represents a unique individual. This means the

files can be easily joined by specimenID and

individualID to get all levels of metadata that apply to a

particular data file. We will use the left_join() function

from the dplyr package, and the %\>%

operator from the magrittr package. If you are unfamiliar

with the pipe, think of it as a shorthand for “take this (the preceding

object) and do that (the subsequent command)”. See magrittr for more info on

piping in R.

R

# join all the rows in the assay metadata

# that have a match in the biospecimen metadata

joined_meta <- rna_meta %>% # start with the rnaseq assay metadata

left_join(bio_meta, by = "specimenID") %>% # join rows from biospecimen

# that match specimenID

left_join(ind_meta, by = "individualID") # join rows from individual

# that match individualID

joined_meta

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 72 × 53

specimenID platform RIN rnaBatch libraryBatch sequencingBatch libraryPrep

<chr> <chr> <lgl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr>

1 32043rh IlluminaN… NA 1 1 1 polyAselec…

2 32044rh IlluminaN… NA 1 1 1 polyAselec…

3 32046rh IlluminaN… NA 1 1 1 polyAselec…

4 32047rh IlluminaN… NA 1 1 1 polyAselec…

5 32049rh IlluminaN… NA 1 1 1 polyAselec…

6 32057rh IlluminaN… NA 1 1 1 polyAselec…

7 32061rh IlluminaN… NA 1 1 1 polyAselec…

8 32065rh IlluminaN… NA 1 1 1 polyAselec…

9 32067rh IlluminaN… NA 1 1 1 polyAselec…

10 32070rh IlluminaN… NA 1 1 1 polyAselec…

# ℹ 62 more rows

# ℹ 46 more variables: libraryPreparationMethod <lgl>, isStranded <lgl>,

# readStrandOrigin <lgl>, runType <chr>, readLength <dbl>,

# individualID <dbl>, specimenIdSource <chr>, organ <chr>, tissue <chr>,

# BrodmannArea <lgl>, sampleStatus <chr>, tissueWeight <lgl>,

# tissueVolume <lgl>, nucleicAcidSource <lgl>, cellType <lgl>,

# fastingState <lgl>, isPostMortem <lgl>, samplingAge <lgl>, …We now have a very wide dataframe that contains all the available metadata on each specimen in the RNAseq data from this study. This procedure can be used to join the three types of metadata files for every study in the AD Knowledge Portal, allowing you to filter individuals and specimens as needed based on your analysis criteria!

R

# convert columns of strings to month-date-year format

joined_meta_time <- joined_meta %>%

mutate(dateBirth = mdy(dateBirth), dateDeath = mdy(dateDeath)) %>%

# create a new column that subtracts dateBirth from dateDeath in days,

# then divide by 30 to get months

mutate(timepoint = as.numeric(difftime(dateDeath, dateBirth, units ="days"))/30) %>%

# convert numeric ages to timepoint categories

mutate(timepoint = case_when(timepoint > 10 ~ "12 mo",

timepoint < 10 & timepoint > 5 ~ "6 mo",

timepoint < 5 ~ "4 mo"))

covars_5XFAD <- joined_meta_time %>%

dplyr::select(individualID, specimenID, sex, genotype, timepoint) %>%

distinct() %>%

as.data.frame()

rownames(covars_5XFAD) <- covars_5XFAD$specimenID

head(covars_5XFAD)

OUTPUT

individualID specimenID sex genotype timepoint

32043rh 32043 32043rh female 5XFAD_carrier 12 mo

32044rh 32044 32044rh male 5XFAD_noncarrier 12 mo

32046rh 32046 32046rh male 5XFAD_noncarrier 12 mo

32047rh 32047 32047rh male 5XFAD_noncarrier 12 mo

32049rh 32049 32049rh female 5XFAD_noncarrier 12 mo

32057rh 32057 32057rh female 5XFAD_noncarrier 12 moWe will save joined_meta for the next lesson.

R

saveRDS(covars_5XFAD, file = "data/covars_5XFAD.rds")

Single Specimen files

For files that contain data from a single specimen (e.g. raw sequencing files, raw mass spectra, etc.), we can use the Synapse annotations to associate these files with the appropriate metadata.

Exercise

Use Explore Data to find all RNAseq files from the

Jax.IU.Pitt_5XFAD study. If we filter for data where

Study = "Jax.IU.Pitt_5XFAD" and

Assay = "rnaSeq" we will get a list of 148 files, including

raw fastqs and processed counts data.

We can use the function synGetAnnotations to view the

annotations associated with any file without downloading the file.

R

# the synID of a random fastq file from this list

random_fastq <- "syn22108503"

# extract the annotations as a nested list

fastq_annotations <- synGetAnnotations(random_fastq)

fastq_annotations

The file annotations let us see which study the file is associated

with (Jax.IU.Pitt.5XFAD), which species it is from (mouse),

which assay generated the file (rnaSeq), and a whole bunch of other

properties. Most importantly, single-specimen files are annotated with

the specimenID of the specimen in the file, and the

individualID of the individual that specimen was taken

from. We can use these annotations to link files to the rest of the

metadata, including metadata that is not in annotations. This is

especially helpful for human studies, as potentially identifying

information like age, race, and diagnosis is not included in file

annotations.

R

# find records belonging to the individual this file maps

# to in our joined metadata

joined_meta %>%

filter(`individualID` == fastq_annotations$individualID[[1]])

Annotations during bulk download

When bulk downloading many files, the best practice is to preserve

the download manifest that is generated which lists all the files, their

synIDs, and all their annotations. If using the Synapse R

client, follow the instructions in the Bulk download files section

above.

If we use the “Programmatic Options” tab in the AD Portal download menu to download all 148 rnaSeq files from the 5XFAD study, we would get a table query that looks like this:

R

query <- synTableQuery("SELECT * FROM syn11346063.37

WHERE ( ( \"study\" HAS ( 'Jax.IU.Pitt_5XFAD' ) )

AND ( \"assay\" HAS ( 'rnaSeq' ) ) )")

As we saw previously, this downloads a csv file with the results of our AD Portal query. Opening that file lets us see which specimens are associated with which files:

R

annotations_table <- read_csv(query$filepath,

show_col_types = FALSE)

annotations_table

You could then use

purrr::walk(download_table$id, ~synGet(.x, downloadLocation = ))

to walk through the column of synIDs and download all 148

files. However, because these are large files, it might be preferable to

use the Python client or command line client for increased speed.

Once you’ve downloaded all the files in the id column,

you can link those files to their annotations by the name

column.

We’ll use the “random fastq” that we got annotations for earlier to

avoid downloading the whole 3GB file, we’ll use synGet with

downloadFile = FALSE to get only the Synapse entity

information, rather than the file. If we downloaded the actual file, we

could find it in the directory and search using the filename. Since

we’re just downloading the Synapse entity wrapper object, we’ll use the

file name listed in the object properties.

R

fastq <- synGet(random_fastq, downloadFile = FALSE)

# filter the annotations table to rows that match the fastq filename

annotations_table %>%

filter(name == fastq$properties$name)

Multispecimen files

Multispecimen files in the AD Knowledge Portal are files that contain

data or information from more than one specimen. They are not annotated

with individualIDs or specimenIDs, since these

files may contain numbers of specimens that exceed the annotation

limits. These files are usually processed or summary data (gene counts,

peptide quantifications, etc), and are always annotated with

isMultiSpecimen = TRUE.

If we look at the processed data files in the table of 5XFAD RNAseq

file annotations we just downloaded, we will see that it

isMultiSpecimen = TRUE, but individualID and

specimenID are blank:

R

annotations_table %>%

filter(fileFormat == "txt") %>%

dplyr::select(name, individualID, specimenID, isMultiSpecimen)

The multispecimen file should contain a row or column of

specimenIDs that correspond to the specimenIDs

used in a study’s metadata, as we have seen with the 5XFAD counts

file.

In this example, we take a slice of the counts data to reduce

computation, transpose it so that each row represents a single specimen,

and then join it to the joined metadata by the

specimenID.

R

counts %>%

slice_head(n = 5) %>%

t() %>%

as_tibble(rownames = "specimenID") %>%

left_join(joined_meta, by = "specimenID")

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 73 × 58

specimenID V1 V2 V3 V4 V5 platform RIN rnaBatch libraryBatch

<chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <lgl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 gene_id "ENS… "ENS… "ENS… "ENS… "ENS… <NA> NA NA NA

2 32043rh " 22… "344… " 5… " … " … Illumin… NA 1 1

3 32044rh " … " … "348… " … " 16… Illumin… NA 1 1

4 32046rh " … " … "394… " … " 13… Illumin… NA 1 1

5 32047rh " … " … "308… " … " 12… Illumin… NA 1 1

6 32048rh " 16… "260… " 2… " … " … Illumin… NA 1 1

7 32049rh " … " … "306… " … " 15… Illumin… NA 1 1

8 32050rh " … " … "271… " … " 16… Illumin… NA 1 1

9 32052rh " 19… "337… " 3… " … " … Illumin… NA 1 1

10 32053rh " 14… "206… " 3… " … " … Illumin… NA 1 1

# ℹ 63 more rows

# ℹ 48 more variables: sequencingBatch <dbl>, libraryPrep <chr>,

# libraryPreparationMethod <lgl>, isStranded <lgl>, readStrandOrigin <lgl>,

# runType <chr>, readLength <dbl>, individualID <dbl>,

# specimenIdSource <chr>, organ <chr>, tissue <chr>, BrodmannArea <lgl>,

# sampleStatus <chr>, tissueWeight <lgl>, tissueVolume <lgl>,

# nucleicAcidSource <lgl>, cellType <lgl>, fastingState <lgl>, …Content from Differential expression analysis

Last updated on 2026-03-03 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- What transcriptomic changes do we observe in mouse models carrying AD-related mutations?

Objectives

- Read in a count matrix and metadata.

- Understand the data from AD mouse models

- Format the data for differential analysis

- Perform differential analysis using DESeq2.

- Pathway enrichment of differentially expressed genes

- Save data for next lessons

Differential Expression Analysis

WARNING

Warning: replacing previous import 'S4Arrays::makeNindexFromArrayViewport' by

'DelayedArray::makeNindexFromArrayViewport' when loading 'SummarizedExperiment'Reading Gene Expression Count matrix from previous lesson

In this lesson, we will use the raw counts matrix and metadata downloaded in the previous lesson and will perform differential expression analysis.

R

counts <- read.delim("data/htseqcounts_5XFAD.txt",

check.names = FALSE)

Reading Sample Metadata from Previous Lesson

R

covars <- readRDS("data/covars_5XFAD.rds")

Let’s explore the data:

Let’s look at the top of the metadata.

R

head(covars)

OUTPUT

individualID specimenID sex genotype timepoint

32043rh 32043 32043rh female 5XFAD_carrier 12 mo

32044rh 32044 32044rh male 5XFAD_noncarrier 12 mo

32046rh 32046 32046rh male 5XFAD_noncarrier 12 mo

32047rh 32047 32047rh male 5XFAD_noncarrier 12 mo

32049rh 32049 32049rh female 5XFAD_noncarrier 12 mo

32057rh 32057 32057rh female 5XFAD_noncarrier 12 moidentify distinct groups using sample metadata

R

distinct(covars, sex, genotype, timepoint)

OUTPUT

sex genotype timepoint

32043rh female 5XFAD_carrier 12 mo

32044rh male 5XFAD_noncarrier 12 mo

32049rh female 5XFAD_noncarrier 12 mo

46105rh female 5XFAD_noncarrier 6 mo

46108rh male 5XFAD_noncarrier 6 mo

46131rh female 5XFAD_noncarrier 4 mo

46877rh male 5XFAD_noncarrier 4 mo

46887rh female 5XFAD_carrier 4 mo

32053rh male 5XFAD_carrier 12 mo

46111rh female 5XFAD_carrier 6 mo

46865rh male 5XFAD_carrier 6 mo

46866rh male 5XFAD_carrier 4 moHow many mice were used to produce this data?

R

covars %>%

group_by(sex, genotype, timepoint) %>%

dplyr::count()

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 12 × 4

# Groups: sex, genotype, timepoint [12]

sex genotype timepoint n

<chr> <chr> <chr> <int>

1 female 5XFAD_carrier 12 mo 6

2 female 5XFAD_carrier 4 mo 6

3 female 5XFAD_carrier 6 mo 6

4 female 5XFAD_noncarrier 12 mo 6

5 female 5XFAD_noncarrier 4 mo 6

6 female 5XFAD_noncarrier 6 mo 6

7 male 5XFAD_carrier 12 mo 6

8 male 5XFAD_carrier 4 mo 6

9 male 5XFAD_carrier 6 mo 6

10 male 5XFAD_noncarrier 12 mo 6

11 male 5XFAD_noncarrier 4 mo 6

12 male 5XFAD_noncarrier 6 mo 6How many rows and columns are there in counts?

R

dim(counts)

OUTPUT

[1] 55489 73In the counts matrix, genes are in rows and samples are in columns. Let’s look at the first few rows.

R

head(counts, n=5)

OUTPUT

gene_id 32043rh 32044rh 32046rh 32047rh 32048rh 32049rh 32050rh

1 ENSG00000080815 22554 0 0 0 16700 0 0

2 ENSG00000142192 344489 4 0 1 260935 6 8

3 ENSMUSG00000000001 5061 3483 3941 3088 2756 3067 2711

4 ENSMUSG00000000003 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

5 ENSMUSG00000000028 208 162 138 127 95 154 165

32052rh 32053rh 32057rh 32059rh 32061rh 32062rh 32065rh 32067rh 32068rh

1 19748 14023 0 17062 0 15986 10 0 18584

2 337456 206851 1 264748 0 252248 172 4 300398

3 3334 3841 4068 3306 4076 3732 3940 4238 3257

4 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

5 124 103 164 116 108 134 204 239 148

32070rh 32073rh 32074rh 32075rh 32078rh 32081rh 32088rh 32640rh 46105rh

1 1 0 0 22783 17029 16626 15573 12721 4

2 4 2 9 342655 280968 258597 243373 188818 19

3 3351 3449 4654 4844 3132 3334 3639 3355 4191

4 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

5 159 167 157 211 162 149 160 103 158

46106rh 46107rh 46108rh 46109rh 46110rh 46111rh 46112rh 46113rh 46115rh

1 0 0 0 0 0 17931 0 19087 0

2 0 0 1 5 1 293409 8 273704 1

3 3058 4265 3248 3638 3747 3971 3192 3805 3753

4 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

5 167 199 113 168 175 203 158 108 110

46121rh 46131rh 46132rh 46134rh 46138rh 46141rh 46142rh 46862rh 46863rh

1 0 0 12703 18833 0 18702 17666 0 14834

2 0 1 187975 285048 0 284499 250600 0 218494

3 4134 3059 3116 3853 3682 2844 3466 3442 3300

4 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

5 179 137 145 183 171 138 88 154 157

46865rh 46866rh 46867rh 46868rh 46871rh 46872rh 46873rh 46874rh 46875rh

1 10546 10830 10316 10638 15248 0 0 11608 11561

2 169516 152769 151732 190150 229063 6 1 165941 171303

3 3242 3872 3656 3739 3473 3154 5510 3657 4121

4 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

5 131 152 152 155 140 80 240 148 112

46876rh 46877rh 46878rh 46879rh 46881rh 46882rh 46883rh 46884rh 46885rh

1 0 0 12683 15613 0 14084 20753 0 0

2 0 2 183058 216122 0 199448 306081 0 5

3 3422 3829 3996 4324 2592 2606 4600 2913 3614

4 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

5 147 166 169 215 115 101 174 127 151

46886rh 46887rh 46888rh 46889rh 46890rh 46891rh 46892rh 46893rh 46895rh

1 16639 16072 0 16680 13367 0 25119 92 0

2 242543 258061 0 235530 196721 0 371037 1116 0

3 3294 3719 3899 4173 4008 3037 5967 3459 4262

4 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

5 139 128 210 127 156 116 260 161 189

46896rh 46897rh

1 15934 0

2 235343 6

3 3923 3486

4 0 0

5 179 117As you can see, the gene ids are ENSEMBL IDs. There is some risk that these may not be unique. Let’s check whether any of the gene symbols are duplicated. We will sum the number of duplicated gene symbols.

R

sum(duplicated(rownames(counts)))

OUTPUT

[1] 0The sum equals zero, so there are no duplicated gene symbols, which is good. Similarly, samples should be unique. Once again, let’s verify this:

R

sum(duplicated(colnames(counts)))

OUTPUT

[1] 0Formatting the count matrix

Now, as we see that gene_id is in first column of count

matrix, but we will need only count data in matrix, so we will change

the gene_id column to rownames.

R

# Converting the `gene_id` as `rownames` of `counts` matrix

counts <- counts %>%

column_to_rownames(., var = "gene_id") %>%

as.data.frame()

Let’s confirm if change is done correctly.

R

head(counts, n=5)

OUTPUT

32043rh 32044rh 32046rh 32047rh 32048rh 32049rh 32050rh

ENSG00000080815 22554 0 0 0 16700 0 0

ENSG00000142192 344489 4 0 1 260935 6 8

ENSMUSG00000000001 5061 3483 3941 3088 2756 3067 2711

ENSMUSG00000000003 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

ENSMUSG00000000028 208 162 138 127 95 154 165

32052rh 32053rh 32057rh 32059rh 32061rh 32062rh 32065rh

ENSG00000080815 19748 14023 0 17062 0 15986 10

ENSG00000142192 337456 206851 1 264748 0 252248 172

ENSMUSG00000000001 3334 3841 4068 3306 4076 3732 3940

ENSMUSG00000000003 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

ENSMUSG00000000028 124 103 164 116 108 134 204

32067rh 32068rh 32070rh 32073rh 32074rh 32075rh 32078rh

ENSG00000080815 0 18584 1 0 0 22783 17029

ENSG00000142192 4 300398 4 2 9 342655 280968

ENSMUSG00000000001 4238 3257 3351 3449 4654 4844 3132

ENSMUSG00000000003 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

ENSMUSG00000000028 239 148 159 167 157 211 162

32081rh 32088rh 32640rh 46105rh 46106rh 46107rh 46108rh

ENSG00000080815 16626 15573 12721 4 0 0 0

ENSG00000142192 258597 243373 188818 19 0 0 1

ENSMUSG00000000001 3334 3639 3355 4191 3058 4265 3248

ENSMUSG00000000003 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

ENSMUSG00000000028 149 160 103 158 167 199 113

46109rh 46110rh 46111rh 46112rh 46113rh 46115rh 46121rh

ENSG00000080815 0 0 17931 0 19087 0 0

ENSG00000142192 5 1 293409 8 273704 1 0

ENSMUSG00000000001 3638 3747 3971 3192 3805 3753 4134

ENSMUSG00000000003 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

ENSMUSG00000000028 168 175 203 158 108 110 179

46131rh 46132rh 46134rh 46138rh 46141rh 46142rh 46862rh

ENSG00000080815 0 12703 18833 0 18702 17666 0

ENSG00000142192 1 187975 285048 0 284499 250600 0

ENSMUSG00000000001 3059 3116 3853 3682 2844 3466 3442

ENSMUSG00000000003 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

ENSMUSG00000000028 137 145 183 171 138 88 154

46863rh 46865rh 46866rh 46867rh 46868rh 46871rh 46872rh

ENSG00000080815 14834 10546 10830 10316 10638 15248 0

ENSG00000142192 218494 169516 152769 151732 190150 229063 6

ENSMUSG00000000001 3300 3242 3872 3656 3739 3473 3154

ENSMUSG00000000003 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

ENSMUSG00000000028 157 131 152 152 155 140 80

46873rh 46874rh 46875rh 46876rh 46877rh 46878rh 46879rh

ENSG00000080815 0 11608 11561 0 0 12683 15613

ENSG00000142192 1 165941 171303 0 2 183058 216122

ENSMUSG00000000001 5510 3657 4121 3422 3829 3996 4324

ENSMUSG00000000003 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

ENSMUSG00000000028 240 148 112 147 166 169 215

46881rh 46882rh 46883rh 46884rh 46885rh 46886rh 46887rh

ENSG00000080815 0 14084 20753 0 0 16639 16072

ENSG00000142192 0 199448 306081 0 5 242543 258061

ENSMUSG00000000001 2592 2606 4600 2913 3614 3294 3719

ENSMUSG00000000003 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

ENSMUSG00000000028 115 101 174 127 151 139 128

46888rh 46889rh 46890rh 46891rh 46892rh 46893rh 46895rh

ENSG00000080815 0 16680 13367 0 25119 92 0

ENSG00000142192 0 235530 196721 0 371037 1116 0

ENSMUSG00000000001 3899 4173 4008 3037 5967 3459 4262

ENSMUSG00000000003 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

ENSMUSG00000000028 210 127 156 116 260 161 189

46896rh 46897rh

ENSG00000080815 15934 0

ENSG00000142192 235343 6

ENSMUSG00000000001 3923 3486

ENSMUSG00000000003 0 0

ENSMUSG00000000028 179 117As you can see from count table there are some genes that start with

ENSG and others start with ENSMUSG.

ENSG refers to human gene ENSEMBL id and

ENSMUSG refer to mouse ENSEMBL id. Let’s check how many

gene_ids are NOT from the mouse genome by searching for the

string “MUS” (as in Mus musculus) in the rownames

of the counts matrix.

R

counts[, 1:6] %>%

filter(!str_detect(rownames(.), "MUS"))

OUTPUT

32043rh 32044rh 32046rh 32047rh 32048rh 32049rh

ENSG00000080815 22554 0 0 0 16700 0

ENSG00000142192 344489 4 0 1 260935 6Ok, so we see there are two human genes in out count matrix. Why? What genes are they?

Briefly, the 5xFAD mouse strain harbors two human transgenes APP

(ENSG00000142192) and PSEN1 (ENSG00000080815)

and inserted into exon 2 of the mouse Thy1 gene. To validate 5XFAD

strain and capture expression of human transgene APP and PS1, a custom

mouse genomic sequence was created and we quantified expression of human

as well as mouse App (ENSMUSG00000022892) and Psen1

(ENSMUSG00000019969) genes by our MODEL-AD RNA-Seq

pipeline.

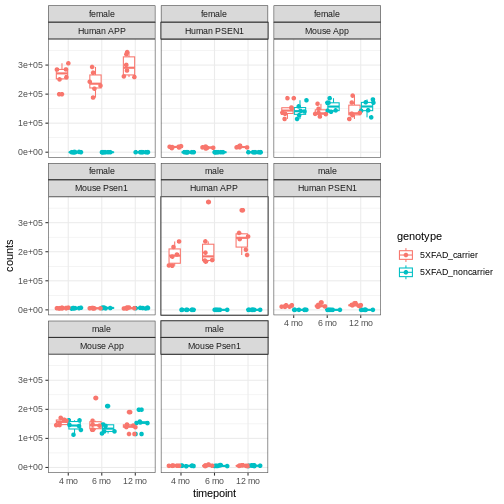

Validation of 5xFAD mouse strain

First we convert the dataframe to longer format and join our

covariates by MouseID.

R

count_tpose <- counts %>%

rownames_to_column(., var = "gene_id") %>%

filter(gene_id %in%

c("ENSG00000080815",

"ENSMUSG00000019969",

"ENSG00000142192",

"ENSMUSG00000022892")) %>%

pivot_longer(., cols = -"gene_id",

names_to = "specimenID",

values_to = "counts") %>%

as.data.frame() %>%

left_join(covars, by="specimenID") %>%

as.data.frame()

head(count_tpose)

OUTPUT

gene_id specimenID counts individualID sex genotype

1 ENSG00000080815 32043rh 22554 32043 female 5XFAD_carrier

2 ENSG00000080815 32044rh 0 32044 male 5XFAD_noncarrier

3 ENSG00000080815 32046rh 0 32046 male 5XFAD_noncarrier

4 ENSG00000080815 32047rh 0 32047 male 5XFAD_noncarrier

5 ENSG00000080815 32048rh 16700 32048 female 5XFAD_carrier

6 ENSG00000080815 32049rh 0 32049 female 5XFAD_noncarrier

timepoint

1 12 mo

2 12 mo

3 12 mo

4 12 mo

5 12 mo

6 12 moRename the APP and PSEN1 genes to specify whether mouse or human.

R

# make the age column a factor and re-order the levels

count_tpose$timepoint <- factor(count_tpose$timepoint,

levels = c("4 mo", "6 mo", "12 mo"))

# rename the gene id to gene symbol

count_tpose$gene_id[count_tpose$gene_id %in% "ENSG00000142192"] <-

"Human APP"

count_tpose$gene_id[count_tpose$gene_id %in% "ENSG00000080815"] <-

"Human PSEN1"

count_tpose$gene_id[count_tpose$gene_id %in% "ENSMUSG00000022892"] <-

"Mouse App"

count_tpose$gene_id[count_tpose$gene_id %in% "ENSMUSG00000019969"] <-

"Mouse Psen1"

Visualize orthologous genes.

R

# Create simple box plots showing normalized counts

# by genotype and time point faceted by sex.

count_tpose %>%

ggplot(aes(x = timepoint, y = counts, color = genotype)) +

geom_boxplot() +

geom_point(position = position_jitterdodge()) +

facet_wrap(~ sex + gene_id) +

theme_bw()

You will notice expression of Human APP is higher in 5XFAD carriers but lower in non-carriers. However mouse App expressed in both 5XFAD carrier and non-carrier.

We are going to sum the counts from both orthologous genes (human APP and mouse App; human PSEN1 and mouse Psen1) and save the summed expression as expression of mouse genes, respectively to match with gene names in control mice.

R

# merge mouse and human APP gene raw count

counts[rownames(counts) %in% "ENSMUSG00000022892", ] <-

counts[rownames(counts) %in% "ENSMUSG00000022892", ] +

counts[rownames(counts) %in% "ENSG00000142192", ]

counts <- counts[!rownames(counts) %in% c("ENSG00000142192"), ]

# merge mouse and human PS1 gene raw count

counts[rownames(counts) %in% "ENSMUSG00000019969", ] <-

counts[rownames(counts) %in% "ENSMUSG00000019969", ] +

counts[rownames(counts) %in% "ENSG00000080815", ]

counts <- counts[!rownames(counts) %in% c("ENSG00000080815"), ]

Let’s verify if expression of both human genes have been merged or not:

R

counts[, 1:6] %>%

filter(!str_detect(rownames(.), "MUS"))

OUTPUT

[1] 32043rh 32044rh 32046rh 32047rh 32048rh 32049rh

<0 rows> (or 0-length row.names)What proportion of genes have zero counts in all samples?

R

gene_sums <- data.frame(gene_id = rownames(counts),

sums = Matrix::rowSums(counts))

sum(gene_sums$sums == 0)

OUTPUT

[1] 9691We can see that 9,691 (17%) genes have no reads at all associated with them. In the next lesson, we will remove genes that have no counts in any samples.

Differential Analysis using DESeq2

Now, after exploring and formatting the data, We will look for differential expression between the control and 5xFAD mice at different ages for both sexes. The differentially expressed genes (DEGs) can inform our understanding of how the 5XFAD mutation affects biological processes.

DESeq2 analysis consist of multiple steps. We are going to briefly understand some of the important steps using a subset of data and then we will perform differential analysis on the whole dataset.

First, order the data (so counts and metadata specimenID

orders match) and save as another variable name.

R

rawdata <- counts[, sort(colnames(counts))]

metadata <- covars[sort(rownames(covars)), ]

Subset the counts matrix and sample metadata to include only 12-month old male mice. You can amend the code to compare wild type and 5XFAD mice from either sex, at any time point.

R

meta.12M.Male <- metadata[(metadata$sex == "male" &

metadata$timepoint == "12 mo"), ]

meta.12M.Male

OUTPUT

individualID specimenID sex genotype timepoint

32044rh 32044 32044rh male 5XFAD_noncarrier 12 mo

32046rh 32046 32046rh male 5XFAD_noncarrier 12 mo

32047rh 32047 32047rh male 5XFAD_noncarrier 12 mo

32053rh 32053 32053rh male 5XFAD_carrier 12 mo

32059rh 32059 32059rh male 5XFAD_carrier 12 mo

32061rh 32061 32061rh male 5XFAD_noncarrier 12 mo

32062rh 32062 32062rh male 5XFAD_carrier 12 mo

32073rh 32073 32073rh male 5XFAD_noncarrier 12 mo

32074rh 32074 32074rh male 5XFAD_noncarrier 12 mo

32075rh 32075 32075rh male 5XFAD_carrier 12 mo

32088rh 32088 32088rh male 5XFAD_carrier 12 mo

32640rh 32640 32640rh male 5XFAD_carrier 12 moR

dat <- as.matrix(rawdata[ , colnames(rawdata) %in%

rownames(meta.12M.Male)])

colnames(dat)

OUTPUT

[1] "32044rh" "32046rh" "32047rh" "32053rh" "32059rh" "32061rh" "32062rh"

[8] "32073rh" "32074rh" "32075rh" "32088rh" "32640rh"R

rownames(meta.12M.Male)

OUTPUT

[1] "32044rh" "32046rh" "32047rh" "32053rh" "32059rh" "32061rh" "32062rh"

[8] "32073rh" "32074rh" "32075rh" "32088rh" "32640rh"R

match(colnames(dat), rownames(meta.12M.Male))

OUTPUT

[1] 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12Next, we build the DESeqDataSet using the following

function:

R

ddsHTSeq <- DESeqDataSetFromMatrix(countData = dat,

colData = meta.12M.Male,

design = ~ genotype)

WARNING

Warning in DESeqDataSet(se, design = design, ignoreRank): some variables in

design formula are characters, converting to factorsR

ddsHTSeq

OUTPUT

class: DESeqDataSet

dim: 55487 12

metadata(1): version

assays(1): counts

rownames(55487): ENSMUSG00000000001 ENSMUSG00000000003 ...

ENSMUSG00000118487 ENSMUSG00000118488

rowData names(0):

colnames(12): 32044rh 32046rh ... 32088rh 32640rh

colData names(5): individualID specimenID sex genotype timepointPre-filtering

While it is not necessary to pre-filter low count genes before running the DESeq2 functions, there are two reasons which make pre-filtering useful: by removing rows in which there are very few reads, we reduce the memory size of the dds data object, and we increase the speed of the transformation and testing functions within DESeq2. It can also improve visualizations, as features with no information for differential expression are not plotted.

Here we perform a minimal pre-filtering to keep only rows that have at least 10 reads total.

R

ddsHTSeq <- ddsHTSeq[rowSums(counts(ddsHTSeq)) >= 10, ]

ddsHTSeq

OUTPUT

class: DESeqDataSet

dim: 33059 12

metadata(1): version

assays(1): counts

rownames(33059): ENSMUSG00000000001 ENSMUSG00000000028 ...

ENSMUSG00000118486 ENSMUSG00000118487

rowData names(0):

colnames(12): 32044rh 32046rh ... 32088rh 32640rh

colData names(5): individualID specimenID sex genotype timepointReference level

By default, R will choose a reference level for factors based on

alphabetical order. Then, if you never tell the DESeq2

functions which level you want to compare against (e.g. which

level represents the control group), the comparisons will be based on

the alphabetical order of the levels.

R

# specifying the reference-level to `5XFAD_noncarrier`

ddsHTSeq$genotype <- relevel(ddsHTSeq$genotype, ref = "5XFAD_noncarrier")

Run the standard differential expression analysis steps that is

wrapped into a single function, DESeq.

R

dds <- DESeq(ddsHTSeq, parallel = TRUE)

OUTPUT

estimating size factorsOUTPUT

estimating dispersionsOUTPUT

gene-wise dispersion estimates: 2 workersOUTPUT

mean-dispersion relationshipOUTPUT

final dispersion estimates, fitting model and testing: 2 workersResults tables are generated using the function results, which

extracts a results table with log2 fold changes, p-values and adjusted

p-values. By default the argument alpha is set to 0.1. If

the adjusted p-value cutoff will be a value other than 0.1, alpha should

be set to that value:

R

res <- results(dds, alpha=0.05) # setting 0.05 as significant threshold

res

OUTPUT

log2 fold change (MLE): genotype 5XFAD carrier vs 5XFAD noncarrier

Wald test p-value: genotype 5XFAD carrier vs 5XFAD noncarrier

DataFrame with 33059 rows and 6 columns

baseMean log2FoldChange lfcSE stat pvalue

<numeric> <numeric> <numeric> <numeric> <numeric>

ENSMUSG00000000001 3737.9009 0.0148125 0.0466948 0.317219 0.7510777

ENSMUSG00000000028 138.5635 -0.0712500 0.1550131 -0.459639 0.6457754

ENSMUSG00000000031 29.2983 0.6705922 0.3563442 1.881866 0.0598541

ENSMUSG00000000037 123.6482 -0.2184054 0.1554362 -1.405113 0.1599876

ENSMUSG00000000049 15.1733 0.3657555 0.3924376 0.932010 0.3513316

... ... ... ... ... ...

ENSMUSG00000118473 1.18647 -0.377971 1.531586 -0.246784 0.805075

ENSMUSG00000118477 59.10359 -0.144081 0.226690 -0.635586 0.525046

ENSMUSG00000118479 24.64566 -0.181992 0.341445 -0.533006 0.594029

ENSMUSG00000118486 1.92048 0.199838 1.253875 0.159376 0.873372

ENSMUSG00000118487 65.78311 -0.191362 0.218593 -0.875427 0.381342

padj

<numeric>

ENSMUSG00000000001 0.943421

ENSMUSG00000000028 0.913991

ENSMUSG00000000031 0.352346

ENSMUSG00000000037 0.566360

ENSMUSG00000000049 0.765640

... ...

ENSMUSG00000118473 NA

ENSMUSG00000118477 0.863565

ENSMUSG00000118479 0.893356

ENSMUSG00000118486 NA

ENSMUSG00000118487 0.785846We can order our results table by the smallest p-value:

R

resOrdered <- res[order(res$pvalue), ]

head(resOrdered, n=10)

OUTPUT

log2 fold change (MLE): genotype 5XFAD carrier vs 5XFAD noncarrier

Wald test p-value: genotype 5XFAD carrier vs 5XFAD noncarrier

DataFrame with 10 rows and 6 columns

baseMean log2FoldChange lfcSE stat pvalue

<numeric> <numeric> <numeric> <numeric> <numeric>

ENSMUSG00000019969 13860.942 1.90740 0.0432685 44.0828 0.00000e+00

ENSMUSG00000030579 2367.096 2.61215 0.0749326 34.8600 2.99982e-266

ENSMUSG00000046805 7073.296 2.12247 0.0635035 33.4229 6.38461e-245

ENSMUSG00000032011 80423.476 1.36195 0.0424007 32.1210 2.24203e-226

ENSMUSG00000022892 271265.838 1.36140 0.0434167 31.3567 7.88742e-216

ENSMUSG00000038642 10323.969 1.69717 0.0549488 30.8864 1.81875e-209

ENSMUSG00000023992 2333.227 2.62290 0.0882819 29.7105 5.61838e-194

ENSMUSG00000079293 761.313 5.12514 0.1738382 29.4822 4.86644e-191

ENSMUSG00000040552 617.149 2.22726 0.0781799 28.4889 1.60609e-178

ENSMUSG00000069516 2604.926 2.34471 0.0847390 27.6697 1.61630e-168

padj

<numeric>

ENSMUSG00000019969 0.00000e+00

ENSMUSG00000030579 3.60954e-262

ENSMUSG00000046805 5.12152e-241

ENSMUSG00000032011 1.34886e-222

ENSMUSG00000022892 3.79622e-212

ENSMUSG00000038642 7.29469e-206

ENSMUSG00000023992 1.93152e-190

ENSMUSG00000079293 1.46389e-187

ENSMUSG00000040552 4.29450e-175

ENSMUSG00000069516 3.88961e-165We can summarize some basic tallies using the summary function.

R

summary(res)

OUTPUT

out of 33059 with nonzero total read count

adjusted p-value < 0.05

LFC > 0 (up) : 1098, 3.3%

LFC < 0 (down) : 505, 1.5%

outliers [1] : 33, 0.1%

low counts [2] : 8961, 27%

(mean count < 8)

[1] see 'cooksCutoff' argument of ?results

[2] see 'independentFiltering' argument of ?resultsHow many adjusted p-values were less than 0.05?

R

sum(res$padj < 0.05, na.rm=TRUE)

OUTPUT

[1] 1603How many adjusted p-values were less than 0.1?

R

sum(res$padj < 0.1, na.rm=TRUE)

OUTPUT

[1] 2001Function to convert ensembleIDs to common gene names

We’ll use a package to translate mouse ENSEMBL IDS to gene names. Run this function and they will be called up when assembling results from the differential expression analysis.

R

map_function.df <- function(x, inputtype, outputtype) {

mapIds( org.Mm.eg.db,

keys = row.names(x),

column = outputtype,

keytype = inputtype,

multiVals = "first")

}

Generating Results table

Here we will call the function to get the symbol names

of the genes incorporated into the results table, along with the columns

we are most interested in.

R

All_res <- as.data.frame(res) %>%

# run map_function to add symbol of gene corresponding to ENSEMBL ID

mutate(symbol = map_function.df(res, "ENSEMBL", "SYMBOL")) %>%

# run map_function to add Entrez ID of gene corresponding to ENSEMBL ID

mutate(EntrezGene = map_function.df(res, "ENSEMBL", "ENTREZID")) %>%

dplyr::select("symbol",

"EntrezGene",

"baseMean",

"log2FoldChange",

"lfcSE",

"stat",

"pvalue",

"padj")

OUTPUT

'select()' returned 1:many mapping between keys and columns

'select()' returned 1:many mapping between keys and columnsR

head(All_res)

OUTPUT

symbol EntrezGene baseMean log2FoldChange lfcSE

ENSMUSG00000000001 Gnai3 14679 3737.90089 0.01481247 0.04669481

ENSMUSG00000000028 Cdc45 12544 138.56354 -0.07125004 0.15501305

ENSMUSG00000000031 H19 14955 29.29832 0.67059217 0.35634418

ENSMUSG00000000037 Scml2 107815 123.64823 -0.21840544 0.15543617

ENSMUSG00000000049 Apoh 11818 15.17325 0.36575555 0.39243756

ENSMUSG00000000056 Narf 67608 5017.30216 -0.06713961 0.04466809

stat pvalue padj

ENSMUSG00000000001 0.3172187 0.75107766 0.9434210

ENSMUSG00000000028 -0.4596390 0.64577537 0.9139907

ENSMUSG00000000031 1.8818665 0.05985415 0.3523459

ENSMUSG00000000037 -1.4051134 0.15998756 0.5663602

ENSMUSG00000000049 0.9320095 0.35133160 0.7656400

ENSMUSG00000000056 -1.5030778 0.13281898 0.5203335Extracting genes that are significantly expressed

Let’s subset all the genes with a p-value < 0.05.

R

dseq_res <- subset(All_res[order(All_res$padj), ], padj < 0.05)

Wow! We have a lot of genes with apparently very strong statistically significant differences between the control and 5xFAD carrier.

R

dim(dseq_res)

OUTPUT

[1] 1603 8R

head(dseq_res)

OUTPUT

symbol EntrezGene baseMean log2FoldChange lfcSE

ENSMUSG00000019969 Psen1 19164 13860.942 1.907397 0.04326854

ENSMUSG00000030579 Tyrobp 22177 2367.096 2.612152 0.07493257

ENSMUSG00000046805 Mpeg1 17476 7073.296 2.122467 0.06350348

ENSMUSG00000032011 Thy1 21838 80423.476 1.361953 0.04240065

ENSMUSG00000022892 App 11820 271265.838 1.361405 0.04341673

ENSMUSG00000038642 Ctss 13040 10323.969 1.697172 0.05494883

stat pvalue padj

ENSMUSG00000019969 44.08277 0.000000e+00 0.000000e+00

ENSMUSG00000030579 34.86004 2.999825e-266 3.609539e-262

ENSMUSG00000046805 33.42285 6.384608e-245 5.121519e-241

ENSMUSG00000032011 32.12104 2.242032e-226 1.348863e-222

ENSMUSG00000022892 31.35669 7.887422e-216 3.796216e-212

ENSMUSG00000038642 30.88640 1.818747e-209 7.294691e-206Exploring and exporting results

Exporting results to CSV files

We can save results file into a csv file like this:

R

write.csv(All_res, file="results/All_5xFAD_12months_male.csv")

write.csv(dseq_res, file="results/DEG_5xFAD_12months_male.csv")

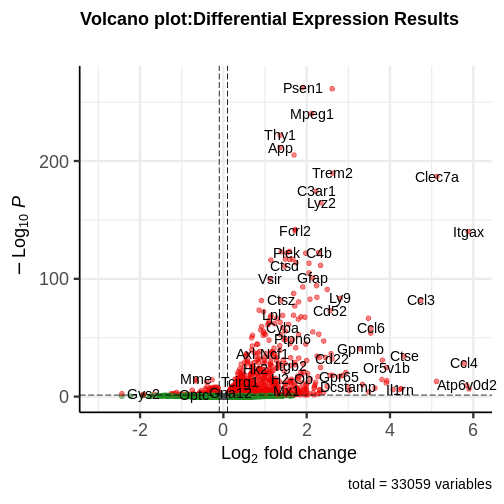

Volcano plot

We can visualize the differential expression results using the

volcano plot function from EnhancedVolcano package. For the

most basic volcano plot, only a single data frame, data matrix, or

tibble of test results is required, containing point labels, log2FC, and

adjusted or unadjusted p-values. The default cut-off for log2FC is

>|2|; the default cut-off for p-value is 10e-6.

R

EnhancedVolcano(All_res,

lab = (All_res$symbol),

x = 'log2FoldChange',

y = 'padj',

legendPosition = 'none',

title = 'Volcano plot:Differential Expression Results',

subtitle = '',

FCcutoff = 0.1,

pCutoff = 0.05,

xlim = c(-3, 6))

WARNING

Warning: One or more p-values is 0. Converting to 10^-1 * current lowest

non-zero p-value...WARNING

Warning: Using `size` aesthetic for lines was deprecated in ggplot2 3.4.0.

ℹ Please use `linewidth` instead.

ℹ The deprecated feature was likely used in the EnhancedVolcano package.

Please report the issue to the authors.

This warning is displayed once per session.

Call `lifecycle::last_lifecycle_warnings()` to see where this warning was

generated.WARNING

Warning: The `size` argument of `element_line()` is deprecated as of ggplot2 3.4.0.

ℹ Please use the `linewidth` argument instead.

ℹ The deprecated feature was likely used in the EnhancedVolcano package.

Please report the issue to the authors.

This warning is displayed once per session.

Call `lifecycle::last_lifecycle_warnings()` to see where this warning was

generated.

You can see that some top significantly expressed are immune/inflammation-related genes such as Ctsd, C4b, Csf1 etc. These genes are upregulated in the 5XFAD strain.

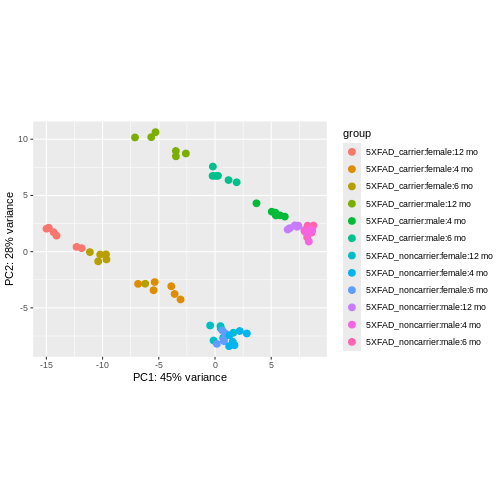

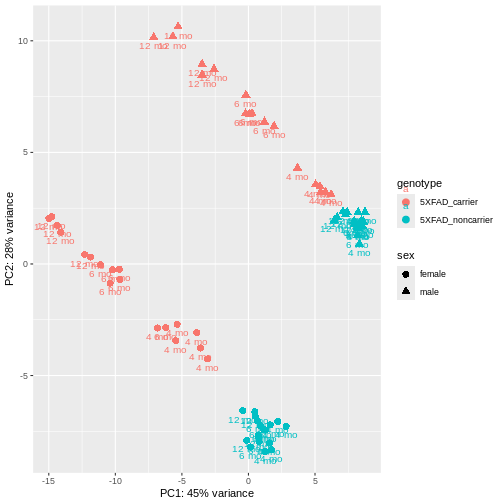

Principal component plot of the samples

Principal component analysis is a dimension reduction technique that reduces the dimensionality of these large matrixes into a linear coordinate system, so that we can more easily visualize what factors are contributing the most to variation in the dataset by graphing the principal components.

R

ddsHTSeq <- DESeqDataSetFromMatrix(countData = as.matrix(rawdata),

colData = metadata,

design = ~ genotype)

WARNING

Warning in DESeqDataSet(se, design = design, ignoreRank): some variables in

design formula are characters, converting to factorsR

ddsHTSeq <- ddsHTSeq[rowSums(counts(ddsHTSeq) > 1) >= 10, ]

dds <- DESeq(ddsHTSeq, parallel = TRUE)

OUTPUT

estimating size factorsOUTPUT

estimating dispersionsOUTPUT

gene-wise dispersion estimates: 2 workersOUTPUT

mean-dispersion relationshipOUTPUT

final dispersion estimates, fitting model and testing: 2 workersOUTPUT

-- replacing outliers and refitting for 42 genes

-- DESeq argument 'minReplicatesForReplace' = 7

-- original counts are preserved in counts(dds)OUTPUT

estimating dispersionsOUTPUT

fitting model and testingR

vsd <- varianceStabilizingTransformation(dds, blind = FALSE)

plotPCA(vsd, intgroup = c("genotype", "sex", "timepoint"))

OUTPUT

using ntop=500 top features by variance

We can see that clustering is occurring, though it’s kind of hard to see exactly how they are clustering in this visualization.

It is also possible to customize the PCA plot using the

ggplot function.

R

pcaData <- plotPCA(vsd,

intgroup = c("genotype", "sex","timepoint"),

returnData = TRUE)

OUTPUT

using ntop=500 top features by varianceR

percentVar <- round(100 * attr(pcaData, "percentVar"))

ggplot(pcaData, aes(PC1, PC2,color = genotype, shape = sex)) +

geom_point(size=3) +

geom_text(aes(label = timepoint), hjust=0.5, vjust=2, size =3.5) +

labs(x = paste0("PC1: ", percentVar[1], "% variance"),

y = paste0("PC2: ", percentVar[2], "% variance"))

PCA identified genotype and sex being a major source of variation in between 5XFAD and WT mice. Female and male samples from the 5XFAD carriers clustered distinctly at all ages, suggesting the presence of sex-biased molecular changes in animals.

Function for Differential analysis using DESeq2

Finally, we can build a function for differential analysis that consists of all above discussed steps. It will require to input sorted raw count matrix, sample metadata and define the reference group.

R

DEG <- function(rawdata, meta, include.batch = FALSE, ref = ref) {

dseq_res <- data.frame()

All_res <- data.frame()

if (include.batch) {

cat("Including batch as covariate\n")

design_formula <- ~ Batch + genotype

}

else {

design_formula <- ~ genotype

}

dat2 <- as.matrix(rawdata[, colnames(rawdata) %in%

rownames(meta)])

ddsHTSeq <- DESeqDataSetFromMatrix(countData = dat2,

colData = meta,

design = design_formula)

ddsHTSeq <- ddsHTSeq[rowSums(counts(ddsHTSeq)) >= 10, ]

ddsHTSeq$genotype <- relevel(ddsHTSeq$genotype, ref = ref)

dds <- DESeq(ddsHTSeq, parallel = TRUE)

res <- results(dds, alpha = 0.05)

#summary(res)

res$symbol <- map_function.df(res,"ENSEMBL","SYMBOL")

res$EntrezGene <- map_function.df(res,"ENSEMBL","ENTREZID")

All_res <<- as.data.frame(res[, c("symbol",

"EntrezGene",

"baseMean",

"log2FoldChange",

"lfcSE",

"stat",

"pvalue",

"padj")])

}

Let’s use this function to analyze all groups present in our data.

Differential Analysis of all groups

First, we add a Group column to our metadata table that

will combine all variables of interest (genotype,

sex, and timepoint) for each sample.

R

metadata$Group <- paste0(metadata$genotype,

"-",

metadata$sex,

"-",

metadata$timepoint)

unique(metadata$Group)

OUTPUT

[1] "5XFAD_carrier-female-12 mo" "5XFAD_noncarrier-male-12 mo"

[3] "5XFAD_noncarrier-female-12 mo" "5XFAD_carrier-male-12 mo"

[5] "5XFAD_noncarrier-female-6 mo" "5XFAD_noncarrier-male-6 mo"

[7] "5XFAD_carrier-female-6 mo" "5XFAD_noncarrier-female-4 mo"

[9] "5XFAD_carrier-female-4 mo" "5XFAD_carrier-male-6 mo"

[11] "5XFAD_carrier-male-4 mo" "5XFAD_noncarrier-male-4 mo" Next, we create a comparison table that has all cases and controls that we would like to compare with each other. Here I have made comparison groups for age and sex-matched 5xFAD carriers vs 5xFAD_noncarriers, with carriers as the cases and noncarriers as the controls:

R

comparisons <- data.frame(control = c("5XFAD_noncarrier-male-4 mo",

"5XFAD_noncarrier-female-4 mo",

"5XFAD_noncarrier-male-6 mo",

"5XFAD_noncarrier-female-6 mo",

"5XFAD_noncarrier-male-12 mo",

"5XFAD_noncarrier-female-12 mo"),

case = c("5XFAD_carrier-male-4 mo",

"5XFAD_carrier-female-4 mo",

"5XFAD_carrier-male-6 mo",

"5XFAD_carrier-female-6 mo",

"5XFAD_carrier-male-12 mo",

"5XFAD_carrier-female-12 mo"))

R

comparisons

OUTPUT

control case

1 5XFAD_noncarrier-male-4 mo 5XFAD_carrier-male-4 mo

2 5XFAD_noncarrier-female-4 mo 5XFAD_carrier-female-4 mo

3 5XFAD_noncarrier-male-6 mo 5XFAD_carrier-male-6 mo

4 5XFAD_noncarrier-female-6 mo 5XFAD_carrier-female-6 mo

5 5XFAD_noncarrier-male-12 mo 5XFAD_carrier-male-12 mo

6 5XFAD_noncarrier-female-12 mo 5XFAD_carrier-female-12 moFinally, we implement our DEG function on each

case/control comparison of interest and store the result table in a list

and data frame:

R

# initiate an empty list and data frame to save results

DE_5xFAD.list <- list()

DE_5xFAD.df <- data.frame()

for (i in 1:nrow(comparisons))

{

meta <- metadata[metadata$Group %in% comparisons[i,],]

DEG(rawdata, meta, ref = "5XFAD_noncarrier")

# append results in data frame

DE_5xFAD.df <- rbind(DE_5xFAD.df,

All_res %>%

mutate(model = "5xFAD",

sex = unique(meta$sex),

age = unique(meta$timepoint)))

# append results in list

DE_5xFAD.list[[i]] <- All_res

names(DE_5xFAD.list)[i] <- paste0(comparisons[i,2])

}

WARNING

Warning in DESeqDataSet(se, design = design, ignoreRank): some variables in

design formula are characters, converting to factorsOUTPUT

estimating size factorsOUTPUT

estimating dispersionsOUTPUT

gene-wise dispersion estimates: 2 workersOUTPUT

mean-dispersion relationshipOUTPUT

final dispersion estimates, fitting model and testing: 2 workersOUTPUT

'select()' returned 1:many mapping between keys and columns

'select()' returned 1:many mapping between keys and columnsWARNING

Warning in DESeqDataSet(se, design = design, ignoreRank): some variables in

design formula are characters, converting to factorsOUTPUT

estimating size factorsOUTPUT

estimating dispersionsOUTPUT

gene-wise dispersion estimates: 2 workersOUTPUT

mean-dispersion relationshipOUTPUT

final dispersion estimates, fitting model and testing: 2 workersOUTPUT

'select()' returned 1:many mapping between keys and columns

'select()' returned 1:many mapping between keys and columnsWARNING

Warning in DESeqDataSet(se, design = design, ignoreRank): some variables in

design formula are characters, converting to factorsOUTPUT

estimating size factorsOUTPUT

estimating dispersionsOUTPUT

gene-wise dispersion estimates: 2 workersOUTPUT

mean-dispersion relationshipOUTPUT

final dispersion estimates, fitting model and testing: 2 workersOUTPUT

'select()' returned 1:many mapping between keys and columns

'select()' returned 1:many mapping between keys and columnsWARNING

Warning in DESeqDataSet(se, design = design, ignoreRank): some variables in

design formula are characters, converting to factorsOUTPUT

estimating size factorsOUTPUT

estimating dispersionsOUTPUT

gene-wise dispersion estimates: 2 workersOUTPUT

mean-dispersion relationshipOUTPUT

final dispersion estimates, fitting model and testing: 2 workersOUTPUT

'select()' returned 1:many mapping between keys and columns

'select()' returned 1:many mapping between keys and columnsWARNING

Warning in DESeqDataSet(se, design = design, ignoreRank): some variables in

design formula are characters, converting to factorsOUTPUT

estimating size factorsOUTPUT

estimating dispersionsOUTPUT

gene-wise dispersion estimates: 2 workersOUTPUT

mean-dispersion relationshipOUTPUT

final dispersion estimates, fitting model and testing: 2 workersOUTPUT

'select()' returned 1:many mapping between keys and columns

'select()' returned 1:many mapping between keys and columnsWARNING

Warning in DESeqDataSet(se, design = design, ignoreRank): some variables in

design formula are characters, converting to factorsOUTPUT

estimating size factorsOUTPUT

estimating dispersionsOUTPUT

gene-wise dispersion estimates: 2 workersOUTPUT

mean-dispersion relationshipOUTPUT

final dispersion estimates, fitting model and testing: 2 workersOUTPUT

'select()' returned 1:many mapping between keys and columns

'select()' returned 1:many mapping between keys and columnsLet’s explore the result stored in our list:

R

names(DE_5xFAD.list)

OUTPUT

[1] "5XFAD_carrier-male-4 mo" "5XFAD_carrier-female-4 mo"

[3] "5XFAD_carrier-male-6 mo" "5XFAD_carrier-female-6 mo"

[5] "5XFAD_carrier-male-12 mo" "5XFAD_carrier-female-12 mo"We can easily extract the result table for any group of interest by

using $ and name of group. Let’s check top few rows from

5XFAD_carrier-male-4 mo group:

R

head(DE_5xFAD.list$`5XFAD_carrier-male-4 mo`)

OUTPUT

symbol EntrezGene baseMean log2FoldChange lfcSE

ENSMUSG00000000001 Gnai3 14679 3707.53159 -0.023085867 0.03816431

ENSMUSG00000000028 Cdc45 12544 159.76225 -0.009444942 0.13226126

ENSMUSG00000000031 H19 14955 35.96987 0.453401511 0.27852555

ENSMUSG00000000037 Scml2 107815 126.82414 0.089394568 0.13774048

ENSMUSG00000000049 Apoh 11818 19.99721 0.115325773 0.31548606

ENSMUSG00000000056 Narf 67608 5344.21741 -0.100413295 0.03811800

stat pvalue padj

ENSMUSG00000000001 -0.60490724 0.545240632 0.9999514

ENSMUSG00000000028 -0.07141125 0.943070457 0.9999514

ENSMUSG00000000031 1.62786329 0.103553876 0.9999514

ENSMUSG00000000037 0.64900725 0.516333691 0.9999514

ENSMUSG00000000049 0.36554951 0.714701258 0.9999514

ENSMUSG00000000056 -2.63427474 0.008431723 0.5696567Let’s check the result stored as dataframe:

R

head(DE_5xFAD.df)

OUTPUT

symbol EntrezGene baseMean log2FoldChange lfcSE

ENSMUSG00000000001 Gnai3 14679 3707.53159 -0.023085867 0.03816431

ENSMUSG00000000028 Cdc45 12544 159.76225 -0.009444942 0.13226126

ENSMUSG00000000031 H19 14955 35.96987 0.453401511 0.27852555

ENSMUSG00000000037 Scml2 107815 126.82414 0.089394568 0.13774048

ENSMUSG00000000049 Apoh 11818 19.99721 0.115325773 0.31548606

ENSMUSG00000000056 Narf 67608 5344.21741 -0.100413295 0.03811800

stat pvalue padj model sex age

ENSMUSG00000000001 -0.60490724 0.545240632 0.9999514 5xFAD male 4 mo

ENSMUSG00000000028 -0.07141125 0.943070457 0.9999514 5xFAD male 4 mo

ENSMUSG00000000031 1.62786329 0.103553876 0.9999514 5xFAD male 4 mo

ENSMUSG00000000037 0.64900725 0.516333691 0.9999514 5xFAD male 4 mo

ENSMUSG00000000049 0.36554951 0.714701258 0.9999514 5xFAD male 4 mo

ENSMUSG00000000056 -2.63427474 0.008431723 0.5696567 5xFAD male 4 moCheck if result is present for all ages:

R

unique((DE_5xFAD.df$age))

OUTPUT

[1] "4 mo" "6 mo" "12 mo"Check if result is present for both sexes:

R

unique((DE_5xFAD.df$sex))

OUTPUT

[1] "male" "female"Check number of genes in each group:

R

dplyr::count(DE_5xFAD.df, model, sex, age)

OUTPUT

model sex age n

1 5xFAD female 12 mo 33120

2 5xFAD female 4 mo 32930

3 5xFAD female 6 mo 33249

4 5xFAD male 12 mo 33059

5 5xFAD male 4 mo 33119

6 5xFAD male 6 mo 33375Check number of genes significantly differentially expressed in all cases compared to age and sex-matched controls:

R

degs.up <- map(DE_5xFAD.list,

~ length(which(.x$padj < 0.05 &

.x$log2FoldChange > 0)))

degs.down <- map(DE_5xFAD.list,

~ length(which(.x$padj < 0.05 &

.x$log2FoldChange < 0)))

deg <- data.frame(Case = names(degs.up),

Up_DEGs.pval.05 = as.vector(unlist(degs.up)),

Down_DEGs.pval.05 = as.vector(unlist(degs.down)))

knitr::kable(deg)

| Case | Up_DEGs.pval.05 | Down_DEGs.pval.05 |

|---|---|---|

| 5XFAD_carrier-male-4 mo | 86 | 11 |

| 5XFAD_carrier-female-4 mo | 522 | 90 |

| 5XFAD_carrier-male-6 mo | 714 | 488 |

| 5XFAD_carrier-female-6 mo | 1081 | 409 |

| 5XFAD_carrier-male-12 mo | 1098 | 505 |

| 5XFAD_carrier-female-12 mo | 1494 | 1023 |

Interestingly, in females more genes are differentially expressed at all age groups, and more genes are differentially expressed the older the mice get in both sexes.

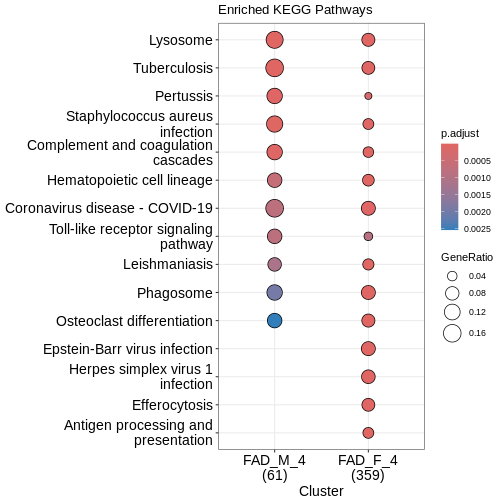

Pathway Enrichment

We may wish to look for enrichment of biological pathways in a list

of differentially expressed genes. Here we will test for enrichment of

KEGG pathways using using the enrichKEGG function in the

clusterProfiler package.

R

dat <- list(FAD_M_4 = subset(DE_5xFAD.list$`5XFAD_carrier-male-4 mo`[order(DE_5xFAD.list$`5XFAD_carrier-male-4 mo`$padj), ],

padj < 0.05) %>%

pull(EntrezGene),

FAD_F_4 = subset(DE_5xFAD.list$`5XFAD_carrier-female-4 mo`[order(DE_5xFAD.list$`5XFAD_carrier-female-4 mo`$padj), ],

padj < 0.05) %>%

pull(EntrezGene))

# perform enrichment analysis

enrich_pathway <- compareCluster(dat,

fun = "enrichKEGG",

pvalueCutoff = 0.05,

organism = "mmu"

)

enrich_pathway@compareClusterResult$Description <-

gsub(" - Mus musculus \\(house mouse)",

"",

enrich_pathway@compareClusterResult$Description)

Let’s plot top enriched functions using the dotplot

function of the clusterProfiler package.

R

clusterProfiler::dotplot(enrich_pathway,

showCategory = 10,

font.size = 14,

title = "Enriched KEGG Pathways")

What does this plot infer?

Save Data for Next Lesson

We will use the results data in the next lesson. Save it now and we

will load it at the beginning of the next lesson. We will use R’s

save command to save the objects in compressed, binary

format. The save command is useful when you want to save

multiple objects in one file.

R

save(DE_5xFAD.df, DE_5xFAD.list, file = "results/DEAnalysis_5XFAD.Rdata")

Content from Cross Species Functional Alignment

Last updated on 2026-03-03 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How do we perfrom a cross-species comparison?

- What transcriptomic changes do we observe in mouse models?

- Which aspects of disease does a model capture?

Objectives

- Approaches to align mouse data to human data

- Understand the human AD co-expression modules

- Understand the data from AD mouse models

- Perform differential analysis using DESeq2

- Perform correlation analysis between mouse models and human modules

- Understand the biological domains and subdomains of AD

- Use domain annotations to compare between species

Author: Gregory Cary, Jackson Laboratory

Setup

First, let’s install the necessary packages into the workspace, starting with the annotation packages:

R

# Mouse and Human annotation databases

# BiocManager::install(c('org.Mm.eg.db','org.Hs.eg.db', 'GO.db'))

Next we’ll install the fgsea and

clusterProfiler packages, which will be used for GO term

enrichment.

R

# fgsea package

# BiocManager::install(c('fgsea', 'clusterProfiler'))

Finally we can instally the synapseclient python package

using the reticulate R package, this will enable us

comand-line access to objects in the Synapse data repository.

R

# synapseclient python package

# reticulate::py_install('synapseclient')

Finally we’ll need to generate a personal access token on Synapse.

Login to Synapse, go to

Your Account > Account Settings > Personal Access Tokens > Manage Personal Access Tokens.

Click on Create New Token and make sure to enable both View

and Download permissions. Paste the resulting PAT in the quotes below

and save it to your workspace.

R

# synToken <-

NOTE: This is for learning purposes only. Storing

your PAT in an environmental variable in your workspace is not secure

and you could easily loose access to the PAT. The preferred method is to

store it in a separate file called .synapseConfig under

your home directory.

Now we should be able to login to Synapse through our R session using the following commands:

R

# import the synapseclient python package

syn.client <- reticulate::import('synapseclient')

syn <- syn.client$Synapse()

# log in to Synapse

# syn$login('', authToken = synToken)

Finally, let’s load the R packages we’ll need for today’s lesson:

R

# load necessary libraries for the analysis

suppressPackageStartupMessages( library(DESeq2) )

suppressPackageStartupMessages( library(org.Mm.eg.db) )

suppressPackageStartupMessages( library(org.Hs.eg.db) )

suppressPackageStartupMessages( library(clusterProfiler) )

suppressPackageStartupMessages( library(fgsea) )

suppressPackageStartupMessages( library(tidyverse) )

# set ggplot plotting theme (personal preference)

theme_set( theme_bw() )

[1] Aligning Human and Mouse Phenotypes

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is complex, and we can not expect any single animal model to fully recapitulate all aspects of late onset AD (LOAD) pathology. To study AD with animal models we must find dimensions through which we can align phenotypes between the models and human cohorts. In MODEL-AD we use the following data modalities to identify commonalities between mouse models and human cohorts:

- Imaging (i.e. MRI and PET) to correspond with human imaging studies

(e.g. ADNI)

- Neuropathological and biomarker phenotypes

- Lots of ’omics — genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics

The ’omics comparisons allow for very rich comparisons because a significant proportion of genes are shared between these two species. Furthermore, homology at the anatomical and neuropathological levels is less clear.

In this session we will explore several ways to compare ’omics signatures between human AD patients and mouse models. We’ll focus on transcriptomic alignment for this session, but we’ll consider other modalities in later sessions. We’ll consider several different approaches to compare gene expression between human cohorts and model systems:

- Correlation of genes within human co-expression modules

- correlations will be generally weak for all expression, but animal

models may recapitulate specific aspects of the disease

- we can use subsets of genes from co-expression modules, which

represent genes expressed in similar patterns in AD, and look for

correlations within these subsets

- Correlation of functional enrichment results

- another approach is to consider the functional annotation enriched among differentially expressed genes in human and mouse.

- we can similarly sub-divide these groups of co-functional genes into biological domains to aid our interpretation

Let’s start by briefly reviewing how to assess differential

expression in our mouse RNA-seq datasets using the DESeq2

package. Then we’ll move on to discussing the background of the human

cohorts and co-expression modules.

[2] Differential Expression Analysis in AD Mouse Models

Let’s analyze the 5xFAD RNA-seq expression data we explored yesterday. Specifically, we want to know which genes are differentially expressed at each age as a result of the transgenes that constitute the 5xFAD model.

The 5xFAD mouse model is a 5x transgenic model consisting of mutatnt human transgenes of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) and presenilin 1 (PSEN1) genes. The specific variants are all causal variants for Familial Alzheimer’s Disease (FAD) and include three variants in the APP gene - Swedish (K670N, M671L), Florida (I716V), and London (V717I) - and two in the PSEN1 gene - M146L and L286V. The expression of both transgenes is under control of the neural-specific elements of the mouse Thy1 promoter, which drives overexpression of the transgenes in the brain. More information about this generation and maintenance of this strain can be obtained from the JAX strain catalog.

This model has been extensively characterized by the MODEL-AD consortium, and others, including the study that we explored yesterday (i.e. syn21983020). For more information about this specific MODEL-AD study, see the publication by Oblak et al (2021). The primary patho-physiological phenotypes are summarized in the figure below from AlzForum, and include (1) early deposition of amyloid plaques, (2) gliosis and neuroinflammation, (3) synaptic changes and cognitive impairment, and (4) neuronal loss, specifically in cortical layer V and the subiculum. Importantly, Tau tangles are absent from this model.

But what else can the RNA-seq data tell us about the

transcriptomic response to the 5xFAD model in the brain? To know more,

we need to assess the differentially expressed transcripts. We’ll use

the DESeq2 package to perform differential expression

analysis of the 5xFAD RNA-seq data.

read 5xFAD RNA-seq count data

First, let’s re-access the RNA-seq data and metadata from Synapse

R

# RNA-seq counts

counts <- syn$get('syn22108847') %>% .$path %>% read_tsv()

# biospecimen metadata

meta <- syn$get('syn22103213') %>% .$path %>% read_csv() %>%

select(individualID, specimenID)

counts <- read_tsv("data/htseqcounts_5XFAD.txt",

show_col_types = FALSE)

# individual metadata

ind_meta <- read_csv("data/Jax.IU.Pitt_5XFAD_individual_metadata.csv",

show_col_types = FALSE)

# biospecimen metadata

bio_meta <- read_csv("data/Jax.IU.Pitt_5XFAD_biospecimen_metadata.csv",

show_col_types = FALSE)

# assay metadata

rna_meta <- read_csv("data/Jax.IU.Pitt_5XFAD_assay_RNAseq_metadata.csv",

show_col_types = FALSE)

# individual metadata, joined to the above

meta <- syn$get('syn22103212') %>% .$path %>% read_csv() %>%

left_join(., meta, by = 'individualID') %>%

filter(!is.na(specimenID))

We can modify the metadata to only include covariates we’ll need for this analysis

R

# order rows that have corresponding IDs in the counts table

covars <- meta %>% slice( match(colnames(counts[,-1]), specimenID) )

# compute the age of animals in months

covars <- covars %>%

mutate(

dateBirth = mdy(dateBirth),

dateDeath = mdy(dateDeath),

age = interval(dateBirth,dateDeath) %/% months(1))

# change the group variable based on the animal genotype

covars <- covars %>%

mutate( group = if_else(genotype == '5XFAD_carrier', '5xFAD', 'WT') )

# finally, only keep the columns we'll need

covars <- covars %>% select(specimenID, group, sex, age)

head(covars)

First, let’s make sure we have all relevant metadata

R

all(colnames(counts[,-1])==covars$specimenID)

How many animals do we have in each group?

R

covars %>% group_by(group, age, sex) %>% summarise(n = n())

Looks like we have 6 samples each from two genotypes (5xFAD or WT), three ages (4 months, 6 months, and 10 months), and both sexes, for a total of 72 samples.

accounting for transgenes

The 5xFAD model has two copies each of the APP and PSEN1 genes - one endogenous mouse gene, and the orthologous human transgene. The RNA-seq data was assessed using a custom transcriptome definition that included the sequences of both the mouse and human versions of each gene.

Ultimately we are going to sum the counts from both ortholgous genes (human APP and mouse App; human PSEN1 and mouse Psen1). But first, let’s look at the expression of each of these genes in the different groups. To start we’ll filter the counts down to just those four relevant gene IDs and join the counts up with the covariates to explore the expression of these genes.

R

tg.counts <- counts %>%

filter(gene_id %in% c("ENSG00000080815","ENSMUSG00000019969",

"ENSG00000142192","ENSMUSG00000022892")) %>%

pivot_longer(.,cols = -"gene_id",names_to = "specimenID",values_to="counts") %>%

left_join(covars ,by="specimenID")

head(tg.counts)

Let’s do a little data housekeeping:

R

# make an age column that is a factor and re-order the levels

tg.counts <- tg.counts %>%

mutate(

age.m = str_c(age, 'm'),

age.m = factor(age.m, levels = c('4m','6m','10m'))

)

# add gene symbols

tg.counts <- tg.counts %>%

mutate(

symbol = case_when(

gene_id == "ENSG00000142192" ~ "Human APP",

gene_id == "ENSG00000080815" ~ "Human PSEN1",

gene_id == "ENSMUSG00000022892" ~ "Mouse App",

gene_id == "ENSMUSG00000019969" ~ "Mouse Psen1"

)

)

Okay, now let’s plot the counts for each gene across the samples:

R

ggplot(tg.counts, aes(x=age.m, y=counts, color=group, shape = sex)) +

geom_boxplot() +

geom_point(position=position_jitterdodge())+

facet_wrap(~symbol, scales = 'free')+

theme_bw()

The human transgenes all have a counts of zero in the WT animals (where the transgenes are absent), while the endogenous mouse genes are expressed relatively consistently across both groups.

Let’s combine the expression of corresponding human and mouse genes by summing the expression and saving the summed expression as expression of mouse genes, respectively to match with gene names in control mice.

R

# move the gene_id column to rownames, to enable summing across rows

counts <- counts %>% column_to_rownames("gene_id")

#merge mouse and human APP gene raw count

counts[rownames(counts) %in% "ENSMUSG00000022892",] <-

counts[rownames(counts) %in% "ENSMUSG00000022892",] +

counts[rownames(counts) %in% "ENSG00000142192",]

counts <- counts[!rownames(counts) %in% c("ENSG00000142192"),]

#merge mouse and human PS1 gene raw count

counts[rownames(counts) %in% "ENSMUSG00000019969",] <-

counts[rownames(counts) %in% "ENSMUSG00000019969",] +

counts[rownames(counts) %in% "ENSG00000080815",]

counts <- counts[!rownames(counts) %in% c("ENSG00000080815"),]

We can confirm that the human genes are now absent from the counts table:

R

counts[,1:6] %>% filter(!str_detect(rownames(.), "MUS"))

prepare data and run DESeq analysis

Next we’ll prepare the data for differential expression analysis. We’ll use DESeq2 today, though there are other approaches. Another disclaimer: there are multiple steps to a DESeq2 analysis and we’re not going to get into nitty-gritty details here. We’ll briefly cover some of the basics, but for more information, please refer to the DESeq2 vignette.

Let’s perform this analysis stratified by age group while controlling for the sex of the animals as a covariate. We can start with the youngest animals (4 months old). Let’s sub-set the data and covariates to these data:

R

covars.4m <- covars %>% filter(age == 4)

counts.4m <- counts[,colnames(counts) %in% covars.4m$specimenID]

Next we’ll build the DESeq object

R

ddsHTSeq <- DESeqDataSetFromMatrix(countData=counts.4m,

colData=covars.4m,

design = ~group+sex)

R

ddsHTSeq

Now we have a DESeqDataSet object covering counts data

for 55k genes across 24 mice.

Let’s take a closer look at the counts that go into this object

R

counts.4m[1:5,1:5]

You can see that ENSMUSG00000000003 has 0 reads across

the samples listed here. Let’s find out how many genes are

0 counts across all samples.

R

gene_sums <- data.frame(gene_id = rownames(counts),

sums = Matrix::rowSums(counts))

sum(gene_sums$sums == 0)

We can see that 9691 (17.5%) genes have no reads at all. Let’s filter these out. While it is not necessary to pre-filter low count genes before running the DESeq2 functions, there are two reasons which make pre-filtering useful: by removing rows in which there are very few reads, we reduce the memory size of the dds data object, and we increase the speed of the transformation and testing functions within DESeq2. It can also improve visualizations, as features with no information for differential expression are not plotted.

Here we perform a minimal pre-filtering to keep only rows that have at least 10 reads in at least 6 separate samples.

R

ddsHTSeq <- ddsHTSeq[rowSums(counts(ddsHTSeq) >= 10) >= 6,]

Challenge 1

What proportion of the 55k genes we started with remain after this filter?

R

ddsHTSeq

There are 24765 genes, or 44.6% (24765/55487).

Let’s also make sure DESeq knows which group is our control or

“reference” group. By default this is arbitrarily assigned to the first

group in the factor. We can use the relevel function to set

the reference group to “WT” (wild type).

R

ddsHTSeq$group <- relevel(ddsHTSeq$group,ref="WT")

Now we’re ready to run the differential expression analysis; it’ll take a few seconds to process this step:

R

dds <- DESeq(ddsHTSeq, parallel = TRUE)

What are the results that have been computed:

R

resultsNames(dds)

Because we specified design = ~ group + sex when setting

up the DESeq object, we now have the results from these two contrasts.

We can pull the results specifically for the 5xFAD vs WT comparison